Have the US election results and the rise of the tech broligarchy got you worried about the morbid symptoms of global patriarchy?

Around the world, various challenges to the liberal international order have emerged that strongly feature expressions of hostile, misogynistic politics. The political elements of Trumpism reverberate in various forms of patriarchal backlash: caricatured pissing contests and brinkmanship between statesmen; manosphere zealots arming themselves for some trad-wife filled, post-immigrant, return to industrial manufacturing utopian future. In the history of patriarchy’s reconstitution, actors appear twice: first as tragedy, then as farce.

There are things that happen to women that the existence of capitalism cannot explain. As materialist feminists, we’ve been frustrated by what J.K. Gibson-Graham calls the “capitalocentrism” of Marxist feminist accounts of women’s historical and contemporary exploitation, depletion, and oppression. Mainstream accounts similarly offer limited tools by which to understand the contemporary moment of patriarchal crisis we see manifesting in: the stalled feminist revolution; various forms of patriarchal backlash emerging globally; and the roll-out of new forms of patriarchal oppression and exploitation.

In our new paper “Morbid Symptoms: A Feminist Dialectics of Global Patriarchy in Crisis,” published in The European Journal of International Relations, we introduce feminist dialectics as a theory and a method for studying patriarchy as a key ordering principle of human societies, constitutive of the international, which accounts for the endurance of patriarchy and changes to its forms over time and across contexts. We offer feminist dialectics as an approach that illuminates, first, the internal relations of various forms of misogynistic and anti-gender resistance that have emerged in the 21st century, and second, what emergent transformation to global patriarchy we may anticipate.

By isolating the internal logics of patriarchy in and of itself, we seek to understand patriarchy through its internal contradictions that give rise to change in form across time and space and manifest in different gender regimes in different contexts. Our feminist dialectics provides the means to study the patriarchy both as a ‘thing’ (the universal ordering logic of social relations) and a relation evolving over time. By adopting a philosophy of internal relations, we seek to situate the apparent discrete ‘parts’ of patriarchal control (whether individual experience, group-level expressions of misogyny, or state instituted gender regimes) within a broader structuring condition of sex class society, patriarchy in general.

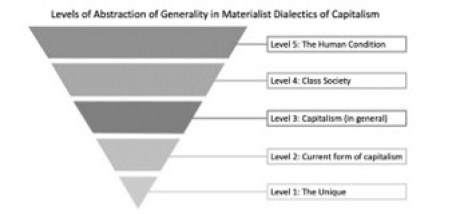

Using levels of abstraction, we can understand patriarchal interpersonal relations and operations of patriarchy at the national level (as a gender regime) while still recognising a general form of patriarchy existing as the ordering condition of the international. While patriarchy is not experienced the same by all individuals around the world, it nonetheless operates as a social force conditioning of all levels of political relations, including the international. Our feminist dialectics allows for both truisms to hold: that patriarchal gender regimes produce different forms of oppression in different contexts, and that we are still living under a gender order we can call patriarchy.

Some feminists have eschewed an analysis of patriarchy as the concept has been critiqued as universal, undifferentiated, timeless, and ahistoric. However, we know that the general and specific conditions of patriarchy have differed and changed dramatically over time and across contexts.

Most accounts of difference between gender regimes and of change to patriarchy in general attribute difference and change in what Ollman refers to as an ‘outside agitator’ – capitalism, mode of production, colonialism, globalisation. These approaches implicitly or explicitly assume that the removal of external conditions will ‘solve’ the problem of patriarchy. In contrast, a dialectical approach attributes “the main responsibility for all change to the inner contradictions of the system or systems in which it occurs” (Ollman, 2015: 18).

Our feminist dialectics reveals a major driving engine of change to patriarchy is contradiction. Patriarchy is full of internal contradictions, such as the fact that it depends on the exploitation of women, but simultaneously undermines and depletes women’s ability to perform social reproduction necessary for its continuance. As well, while patriarchal control rests on the resort to violence to maintain male dominance and female subordination, the very act of performing violence generates consciousness of sexual inequality and undermines women’s consent to the sexual contract, which may foment resistance. It is in the genesis of such antagonisms that the possibility for change emerges.

Thus, we theorise these multiple forms of patriarchal backlash and the stall in the women’s revolution as morbid symptoms signalling the interregnum between patriarchal orders. We don’t see these symptoms as signs of roadblocks in a linear trajectory towards women’s emancipation, but as internal antagonisms that lay the groundwork for and are constitutive of the emergence of a new form of patriarchy.

To bring it back to the broligarchy, rather than a patriarchy regulated and institutionalised by state-based gender regimes, we anticipate the emergent patriarchy to be a technology-mediated form characterised by decentralised, libertarian, unregulated sexual economies. We suggest technology enables a more efficient way to organise patriarchal control of men over women and thus becomes embedded as a mechanism of rule. This emergent form of patriarchal order we call Techno Patriarchy.

In this emerging Techno Patriarchy, we think the new basis of patriarchal control features a share economy in which all men possess property in women’s persons, in contrast to previous modes of patriarchal control residing in individual men as heads of household or mediated by the state. The control becomes diffuse, atomised, stochastic and gives feminist resistance no clear object against which to organise.

We see hints of this emerging techno patriarchy all around us. From the mass penetration of women’s mobile devices by unsolicited dick pics, the advent of so-called ‘revenge porn’, to the objectification of young women in both innocuous forms (Instagram) as well as subscription sexual services (Onlyfans). We see it also in the scientific rationalist pronatalism of Silicon Valley types, concerned with population collapse, which sees huge cultural investment in encouraging women to bear many children, while investing massive amounts of money in reproductive technology start-ups.

While in-depth explorations on the forms and internal contradictions of this emerging Techno Patriarchy are required, we feel it safe to say for now that the patriarchy against which we must mobilise today is not our mother’s patriarchy.

In the art of war, one must know thy ‘main enemy’ in order to more effectively resist. We believe that the tools of our feminist dialectics offer a better means for understanding the internal relations and dynamism of patriarchy, and allow the development of new strategies of feminist mobilisation.

Bernie Masters | Dec 10 2424

Far better to live in countries like Afghanistan and Iran than suffer by living in the imperfect West.